Former Nine Elms fireman DAVE WILSON recalls his experience on the footplate of ‘Merchant Navy’ No. 35022 Holland America Line when it travelled from Waterloo to Yeovil non-stop, 60 years ago.

This is an account of events that took place 60 years ago on February 28 1965 – just two weeks before my 18th birthday.

I had started my footplate career at 55C Farnley Junction as an engine cleaner in April 1962, earning £3 12 0 shillings for a 42-hour week. However, it wasn’t about the money; it was about fulfilling my schoolboy dream and emulating those footplatemen in the tales of Ransome-Wallis, O.S. Nock and so on. To further my footplate ambitions, I left Farnley Junction early in 1963 to move up the ladder from passed cleaner to fireman at the legendary Nine Elms shed, on the Southern Region. I was now firing Bulleid’s ‘Pacifics’ on the types of services that O.S. Nock – whose ‘Locomotive Practice and Performance’ column in The Railway Magazine I avidly read – and of which his contemporaries were recording the performances. The schoolboy dream was now my everyday reality.

The enginemen’s mess room at a big shed like Nine Elms swirls with banter and rumour and, at the beginning of February 1965, the big rumour was that there was to be an attempt to run non-stop from Waterloo to Yeovil. It hadn’t been done before and this was my chance to be the first fireman to do so. I knew the job would go to a top link crew, so I set about finding out which crew it would be and if I could persuade the fireman to swap turns with me. The driver was Arthur ‘Spot’ King and his fireman was a lad called Hennings (Dave?). Driver King had earned his sobriquet ‘Spot’ from his habit of asking his fireman to ‘spot that one for me’ – a request to look out for the next signal, usually a distant signal which could be seen first from the fireman’s side of the footplate.

Persuading fireman Hennings to change turns involved money changing hands because the mileage payment for a trip to Exeter and back was a not inconsiderable sum. Mileage was paid at the rate of one hour’s pay for every 15 miles over 140 miles; the round trip from Nine Elms to Waterloo and Exeter and return was 360 miles – 60 miles further than the crews worked on Euston Carlisle services and worth more than 14 hours of mileage pay! A very generous whip-round from the enthusiasts on the tour meant I wasn’t out of pocket, however.

Having persuaded fireman Hennings to swap turns, the next step was to convince driver King and the running shed foreman that I was up to the task. My regular three-link mate Eric ‘Sooty’ Saunders assured them I was a capable and efficient fireman and could, despite my tender years, be trusted to do the job. I would be the first fireman to work non-stop from Waterloo to Yeovil!

Yeovil and beyond

Our engine for the trip to Exeter and back was ‘Merchant Navy’ No. 35022 Holland America Line – chosen because she was fitted with a 6,000-gallon tender. The Southern Railway did not have any troughs and the distance between Waterloo and Yeovil is 123 miles – at the very top end of the range for a ‘Merchant Navy’ without taking water. Indeed, water consumption was considered so critical that Arthur Jupp, the footplate inspector riding with us on the day, told me before we left Waterloo that if the water had dropped below the tap (less than 3,000 gallons) when we passed Worting Junction we would have to stop at Salisbury for water.

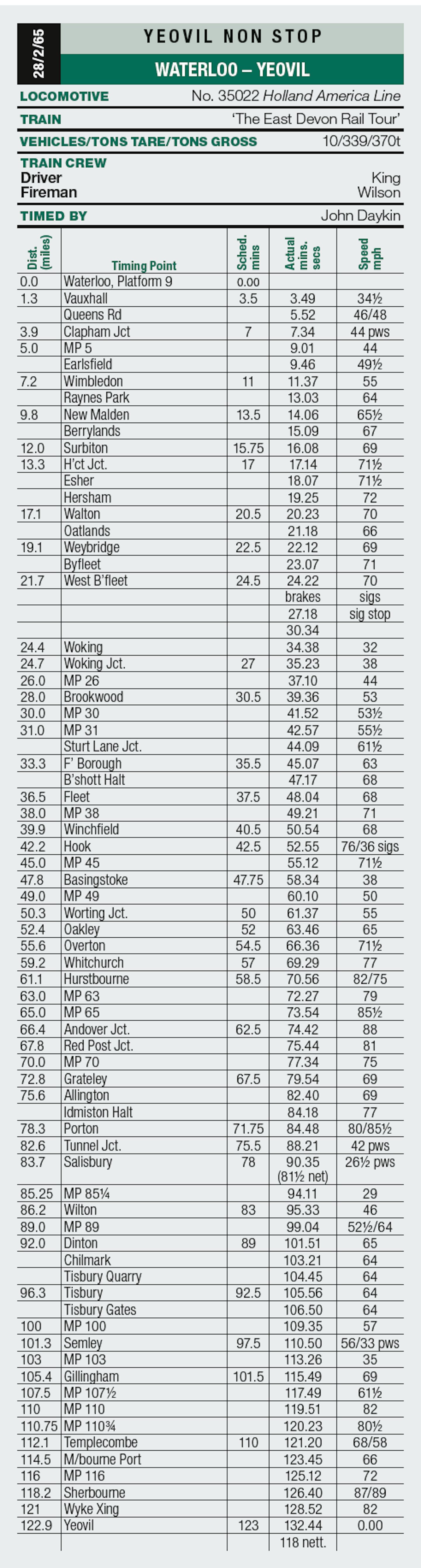

I had insisted on getting my own engine ready – ‘if tha’ wants summat done reet then do it thi’sen’. The 9am start out of Waterloo meant booking on not long after 7 o’clock. We didn’t get back to Waterloo until 8.30pm, 13½ hours after booking on which, added to the mileage and Sunday rates of time and ¾, meant that for the day’s work I would receive 37½ hours pay – almost a week’s wages. However, this was not about the money; it was about being fireman on a rail tour making a record. Thanks to Don Benn, John Daykin and Mark Thomas of the Southern Locomotive Preservation Group, I now have a complete log of the tour, except for the Yeovil Junction to Exeter section of the Down trip.

The schedule for the 122.9 miles to our first stop at Yeovil Junction was 123 minutes – not excessive for a ‘Packet’ with only ten coaches (370 tons tare), but sharp enough when the need to conserve water is taken into consideration. Departure from Waterloo was ‘on time’ if not a minute early and the key to our success would be careful handling of both boiler and engine over the coming miles. This was not going to be a trip on which speed records would be broken but that did not mean that we would be merely trundling along, as the schedule demanded a mile a minute average. After the compulsory 40mph slack through Clapham Junction, the gradient increases up through Earlsfield. From here the serious shovelling begins. Clear of the Clapham slack, driver King began to get No. 35022 into her stride and our speed had risen to 55mph by the time we passed through Wimbledon; it was up to 64mph at Raynes Park and 70mph as Surbiton slid by. As we settled into a steady 70/71mph through Esher, Hersham and Walton, I was firing to a rhythm of six to eight shovels full and then a short break before repeating the pattern but firing different sections of the grate. Driver King was keeping to within seconds of the booked timings and ’22 was steaming well as we approached West Byfleet where we were brought to a dead stop by signals, probably caused by a movement across our path at Woking.

Of all the places one might chose to be stopped by signals, West Byfleet wasn’t one of them. From Byfleet, the drag up to milepost 31 begins to make itself felt – to make matters worse, No. 35022 began to slip as we restarted. Despite the slip, Woking station was cleared at a little over 30mph and milepost 31 was passed at a creditable 55½mph. For the record, being stopped by signals doesn’t mean that the run wasn’t non-stop. Non-stop, as far as the crew are concerned, is that no station or water stops were made between Waterloo and Yeovil.

The little dip down from milepost 31 through Sturt Lane and on to Farnborough saw speed rise back into the 70s just beyond Fleet, and 76 before Hook and another signal check brought speed down to 35mph. Basingstoke was passed in a shade over 58 minutes, 10 minutes down.

With water still in the tap as we cleared Worting Junction, Inspector Jupp gave qualified thumbs up to running through to Yeovil. With the next 15 miles mostly downhill, I had time to wet my whistle with, what by now was, pretty stewed tea; what mattered was it was wet. Whitchurch flashed by at 77mph, Hurstbourne at 82, and Andover Junction at 88mph. Tea break over, it was time to begin putting a few more rounds on ready for the climb to Grateley.

Speed had dropped to 69mph as we passed Grateley but was back up to 77mph as we sped through Idmiston Halt – the station for the Porton Down germ warfare research establishment (trains only stopped by special stop order issued to the driver) – reaching 85mph as Porton itself was passed.

Permanent way slacks at Tunnel Junction and again through Salisbury station saw us passing Wilton at 46mph, 12½ minutes down on our schedule. By the time we passed Dinton, speed was back in the 60s and I was back on the shovel as we climbed the long 1in145 to Semley through which we passed at 57mph. More than 100 miles into our journey, we dashed through Gillingham at 70mph. This was all new railway to me, as Nine Elms crews rarely ventured beyond Salisbury. New railway has its excitement for the enthusiast; for the fireman, it presents problems of when to fire, when will the driver need steam, and when will the running be easy. When you don’t know the road, making these judgements means relying on others to tell you what is coming up over the next few miles.

From Gillingham to Yeovil, the line is punctuated by two short climbs – one from around milepost 106 and another by Templecombe – but in between these humps there is some good running and No. 35022 reached the 90mph mark as we hurtled through Sherbourne. The 17½ miles between Gillingham and our stop for water at Yeovil were covered in a shade under 17 minutes despite a check as we ran into Yeovil itself. The actual start to stop time for the 123 miles from Waterloo to Yeovil was 132 minutes, nine more than the schedule; the net time was 118 minutes, five minutes under the set timing, making our average speed slightly more than a mile a minute.

Learning the hard way

From Yeovil, driver King needed a pilotman as he had not signed the road beyond Yeovil, and so we were joined on the footplate by driver Morley of Yeovil Junction for the run to Axminster where some enthusiasts were to make a tour of the Lyme Regis branch while the remaining tour members went on to Seaton Junction for a trip on the Seaton branch. The trip down the Seaton branch was made using four coaches of the main train, and I persuaded Inspector Jupp and driver King to let me go along for the ride.

Back on the footplate after my jaunt down the Seaton branch, it was time, once again, for some serious graft. Seaton Junction is at the beginning of one of the most difficult banks on the entire route and we were going to be tackling it from a standing start. From Seaton Junction to Honiton is roughly seven miles, the last 4½ miles of which are at 1in80 and then into Honiton tunnel.

When we left Seaton Junction, No. 35022 had been standing idle while the Seaton branch trip was made; this is never a good situation when an engine has been working hard and is then left to sit, as the clinker begins to set and the fire doesn’t get enough air through it. The coal was the dross from the back of the tender and of very mixed quality, with a high dust content. This also adds to the fireman’s difficulties. My abiding memory of the slog up to Honiton summit was working with the dart and the shovel as I struggled to keep 160lbs pressure and a half glass of water, alternating with hanging from the cab window watching for the tunnel and the summit – it was a long 4½ miles. And, I would have to say it wasn’t my finest hour as a fireman, as we dropped time hand over fist all the way up the bank. A lesson learned the hard way.

Next stop was Sidmouth and for the enthusiasts a run down the Sidmouth branch and then round the Exmouth branch back to Exeter. For No. 35022 and us, it was light engine to Exmouth Junction shed where we could eat, drink, and ready ourselves for the long journey home. Meanwhile, an Exmouth Junction crew cleaned the fire, turned, coaled, and watered No. 35022 – and, unwittingly, created the drama which was to occur as we began to climb from Salisbury Tunnel Junction to Grately an hour or so later on our return journey.

A great big lump

Engine and men suitably refreshed, it was time to go off-shed and collect our train. The start from Exeter was 18 minutes late at 4.13pm. Running over foreign metals is hard in daylight; it is even more difficult at night, and again I was depending on the pilotman to let me know when the banks, both up and down, were coming. We were scheduled to take 50 minutes for the 49 miles from Exeter to Yeovil Junction – a tight schedule and one which wasn’t met. We were another six minutes late by the time we stopped for water and parted company with our pilotman. We swapped the pilotman for a footplate visitor – there goes my seat again!

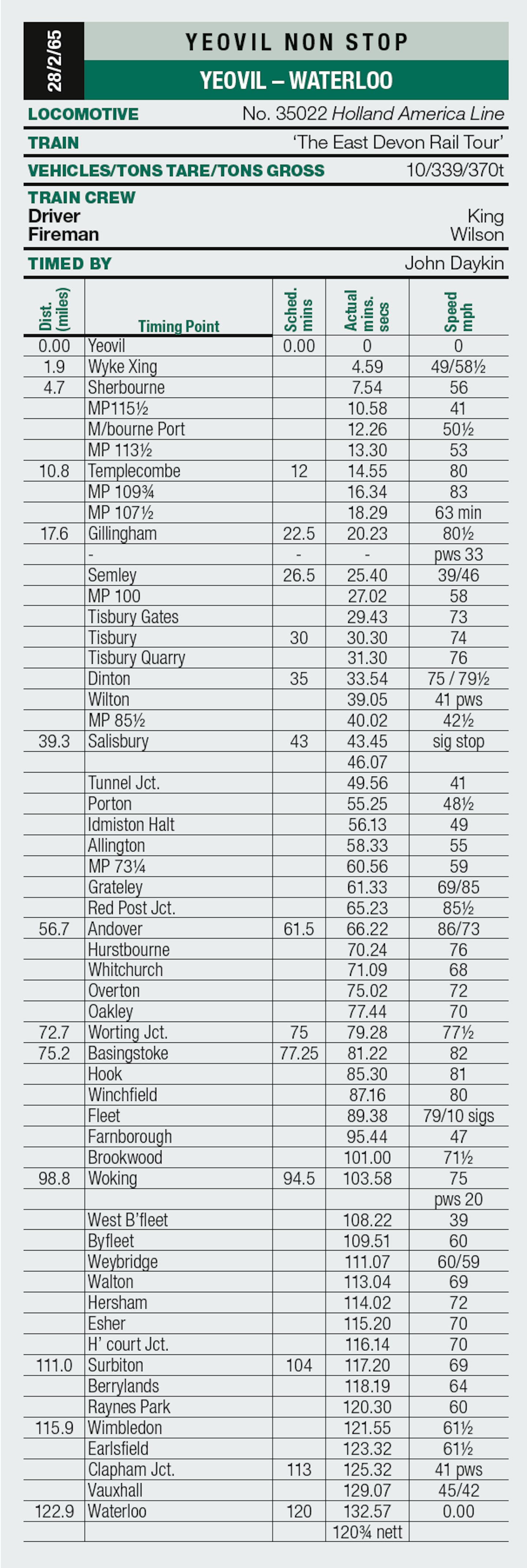

Just as we did on the outward leg, we were to make the run from Yeovil to Waterloo non-stop, and this time the schedule was 121 minutes for the 123 miles. By the time we had finished taking water and were ready for the off, we were 26 minutes late. The 39 miles from Yeovil to Salisbury were scheduled to take 43 minutes, which included a 30mph permanent way slack between Gillingham and Semley. Milepost 100 was passed at just a shade under 60mph and the Tisbury Gates to Dinton section saw speeds of 76mph at Tisbury Quarry and 80mph at Dinton before slowing for a 40mph slack through Wilton.

Despite the check at Wilton, the timings were being kept as we approached Salisbury and a dead stand for signals. The 39.3 miles had taken 43 minutes 45 seconds, a mere 45 seconds down. The signal stop was almost three minutes and, when the ‘right away’ came, we were 29 minutes late. I was back on familiar territory now and I knew just what was coming. Once clear of Salisbury station and tunnel, the line climbs steeply over the next ten miles to Grateley. Once out of the tunnel and past Tunnel Junction Signal Box, the shovelling is near continuous up to Grateley – or at least it would have been had the mother of all lumps of coal not fallen across the shovelling plate, completely blocking it.

Opening the door to the tender, I began to hack at the boulder with the coal pick. The lump refused all attempts to split or crack it – a task hampered by the fact that the coal doors prevented a clean swing. Something was going to have to be done; either we would have to stop in section and deal with the problem, or I could climb through the coal door into the tender while we kept going and then attempt to remove the lump through the coal door. Climbing into the tender when the engine is in motion is not only a serious contravention of the rule book, it is also not recommended from a personal safety pointof-view either. With driver King acting look-out and Inspector Jupp watching my position in the tender I began to wrestle the lump free and onto the footplate. Inspector Jupp and I heaved it whole through the fire door – it wouldn’t fit on the shovel anyway. Not quite copy book firing with double-fist size lumps, but we did keep going.

Over the summit at Grateley, the line descends toward Andover and our speed increased from 69mph through Grateley to 86mph at Red Post Junction, touching 90mph through Andover Junction. From here, there is only the pull up through Hurstbourne and Whitchurch to Overton – just one more concerted effort on the shovel and then easy street all the way to Waterloo. Despite the adverse gradients after passing Andover Junction, speed remained in the 70s except for a brief dip down to 68mph between Whitchurch and Overton. Basingstoke was passed with speed up in the 80s and this was being maintained with some ease until a signal check at Fleet brought us almost, but not quite, to a stand. The 36 miles between Grateley and Fleet had been covered at an average speed of 77mph.

The remainder of the journey back to Waterloo was broken only by a permanent way slack through Woking and the permanent speed restriction through Clapham Junction. Amazingly, the return journey had also taken 132 minutes – just the same as the outward journey from Waterloo to Yeovil – and the net time was 121 minutes, exactly the time scheduled, though our arrival was 39 minutes late.

It had been a long, tiring but enjoyable day. We may not have made it non-stop but we did make the 123 miles without taking water – and it was still two weeks to my 18th birthday!

Each issue of Steam Railway delivers a wealth of information that spans the past, present and future of our beloved railways. Featuring stunning photography, exclusive stories and expert analysis, Steam Railway is a collector's item for every railway enthusiast.

Choose the right subscription for you and get instant digital access to the latest issue.