This year, the Kent & East Sussex Railway celebrated 50 years since it reopened to passengers. However, efforts to preserve it star ted long before – in 1961. One man was there from the start, and he continues to volunteer at the KESR to this day: ALAN CROTTY. This is his story.

INTERVIEW: TIM DUNN WORDS: STEAM RAILWAY

“I grew up in Tenterden from the age of about three months, so I don’t remember anywhere else,” muses Alan Crotty, sitting with his wife Cathy. “There are not many people now left here who can really tell you about that era.

“I suppose that’s why they chose me”, he laughs. Kent’s railways have been in Alan’s blood for many years – on a freezing cold January 2 1954, aged just five, he was taken to watch the last train to work from Tenterden to London, sparking off a lifelong interest that led to him becoming a lynchpin of the Kent & East Sussex Railway (KESR) from the start until the present day.

“Loads of people from town went down to see the last passenger train, which was an ‘O1’ and a ‘Terrier’, [No. 31065, now preserved on the Bluebell Railway and ‘A1X’ ‘Terrier’ No. 32678 preserved here on the KESR], that had worked through from Headcorn, and then it left with a wreath on the front to go down to Rolvenden, where the engines changed because the ‘O1s’ couldn’t work to Robertsbridge. They were too heavy. At Rolvenden they changed to a ‘Terrier’ [No. 32655] which took the last train all the way to Robertsbridge.

“Once the passenger service had finished,” he adds, “the freight service was one train a day, Monday to Friday. It started at Robertsbridge, came up dropping off wagons at the various stations [and] ended up at Tenterden. The main thing carried was coal, because every station had a coal yard. So, all these little 16-tonne mineral wagons full of coal would come up initially with a ‘Terrier’. You couldn’t help but see the train every day as my school playground overlooked Tenterden Town Station”.

Seven years later the first stirrings of what was to become the Kent & East Sussex Railway Preservation Society began when three schoolboys, Tony Hocking, Gardner Crawley and Nick Rose, decided to begin a preservation movement. In their teens, the three held a public meeting at the Rother Valley Hotel in Northiam in April 1961, ahead of the scheduled final passenger train in June.

“It was absolutely the obvious thing to do,” says Alan, “this railway was closing. It had great history, and they didn’t want to run it as a heritage railway. It was going to be a functional railway. I think I started to show an interest in it in about October when they took the lease on Tenterden Town station. Then you get drawn into these things…”

The first time

With his interest piqued, Alan – by now aged 13 – started to take more of an interest, finally venturing over to see what was happening at the old station. Does he still remember that first time?

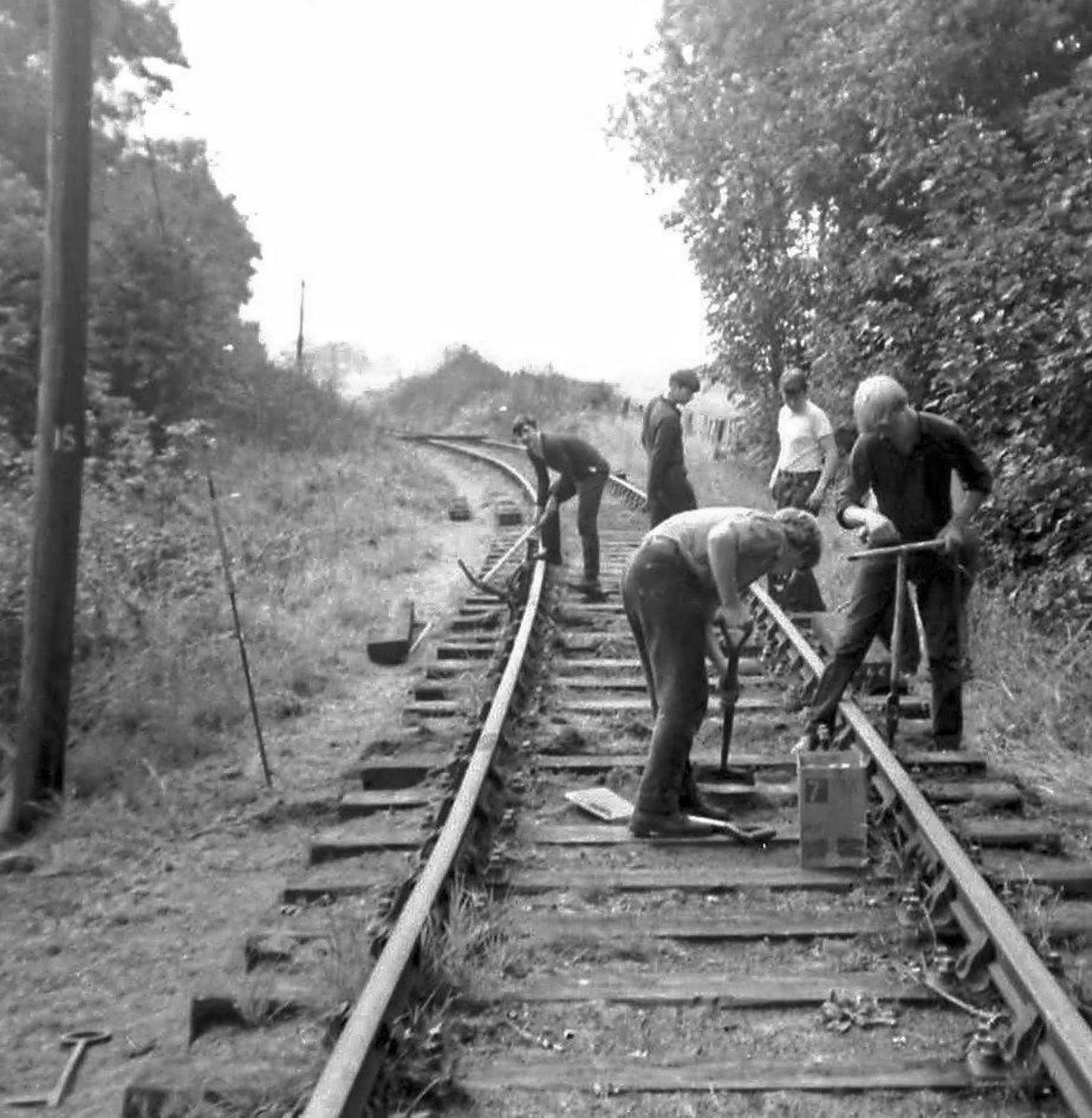

“The first time there were people clearing the station out, literally sweeping the mess out because it had been left for weeks. They swept up and somebody was digging the garden – a platform garden like many little stations in the past. There was no rolling stock at all. The next thing I recall people doing was pulling the weeds up because the track had become overgrown. That would probably have been in the spring of 1962.

“I was interested in engineering. I thought, ‘Oh, there’s some engineering here’. This could be good fun. Then of course, you start to meet the people [Tony, Gardner and Nick], none of whom were engineers at that stage, but they were all dead keen on getting this railway going. By 1962, not only had they got the lease on the station, but they had entered into negotiations to buy the whole railway. Then they formed a guiding committee, if you like, and there wasn’t one person on that committee who was over 22 years old. They were all young. Well, to me [at 13], they were old.”

At this point, Leonard Heath Humphrys – instrumental in starting the Ffestiniog Railway Society – and Robin Doust entered the scene. Alan describes Robin as the ‘leading light’; they started negotiating with British Railways to buy not just the station, but the line itself. By this point the society also had its magazine, written and edited by Robin Doust, which was circulated to some 100 members, although the number was steadily rising. Reactions to Alan’s new pastime were positive, and soon he started bringing others along.

“Some of them thought I was mad. Another couple of lads from school came as well. They came and joined because I said, ‘Hey, I found this.’ I’m still in contact with some, even though they don’t live in Tenterden anymore. They came because they thought it was fun. I mean, what do you do in a small town like Tenterden when you’re a teenager? There wasn’t much else.”

The following year another organisation – the Kent and Sussex Locomotive Trust – was formed to buy two more engines, together with a six-wheeled SECR brake van previously used by the railway at the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough. “It was £51 10s and 6d because we sat and said, ‘How much are we going to tender,’ for it? Somebody said, ‘Oh, £50.’ Ron Cann, who was in his forties, so he was ‘very old’, said, ‘Oh, that’s too much for a round figure. A scrap man will do that.’ So, somebody said, ‘Well, if we said £51, and somebody said ten shillings, and someone else said sixpence.’ That’s what we tendered. We raised the money from a whip-round [of members] basically.”

At the same time, money was being raised to pay for the lease on the Tenterden station buildings and yard.

“It came from subscriptions,” recalls Alan, “the society charged a guinea for adults and 10s and 6d for junior members. I was a junior member. I was member number 50, and I still have my number 50. So that’s where the income came from, plus donations.”

Community vision

At this stage the aim was for the railway to reopen for the benefit of the community – it was to be a ‘proper’ railway. Less consideration was given to the historical side of things, and more to the practicalities of a transport lifeline for Tenterden.

“I think everybody believed you could do that,” agrees Alan. “You could do it then because wagonload freight was still the thing. Just.

It petered out by 1968. Back in 1961, there was a flour mill [at the other end of the line at Northbridge] called Hodson’s Mill. It had a daily delivery of grain by rail. When the railway closed that year, the mill still needed to get its grain in, and it came in bulk grain tankers.”

The flour mill also led to the delivery of a ‘P’ class engine – No. 31556 – from British Railways.

“Mr Dadswell, the man who owned the mill, decided to buy an engine to collect the grain tankers from Robertsbridge station and haul them to the mill. So, he rang up British Railways, as you do, and said, ‘Well, you’ve shut the railway, but I still need to get my stuff in.’ So he bought No. 1556, and things became much simpler! His maintenance man – Mr Barber – had to look after it, but he didn’t really know anything about steam engines. However, he knew about engineering, so it was duly delivered.

“Mr Barber wanted to find out how to work it. So, he spoke to the village policeman who had been a fireman at Tonbridge shed and who cycled down to the mill one Sunday to show Mr Barber how to fire and drive the engine. Even though the railway had closed, British Railways still delivered grain tankers to the yard at Robertsbridge. Mr Barber would light the ‘P’ class up, pop over the road, and go up to the station to collect the grain tankers and move them into the mill – a distance of about half a mile.”

At this stage, the society was not allowed to run anything – the site was merely leased from British Railways.

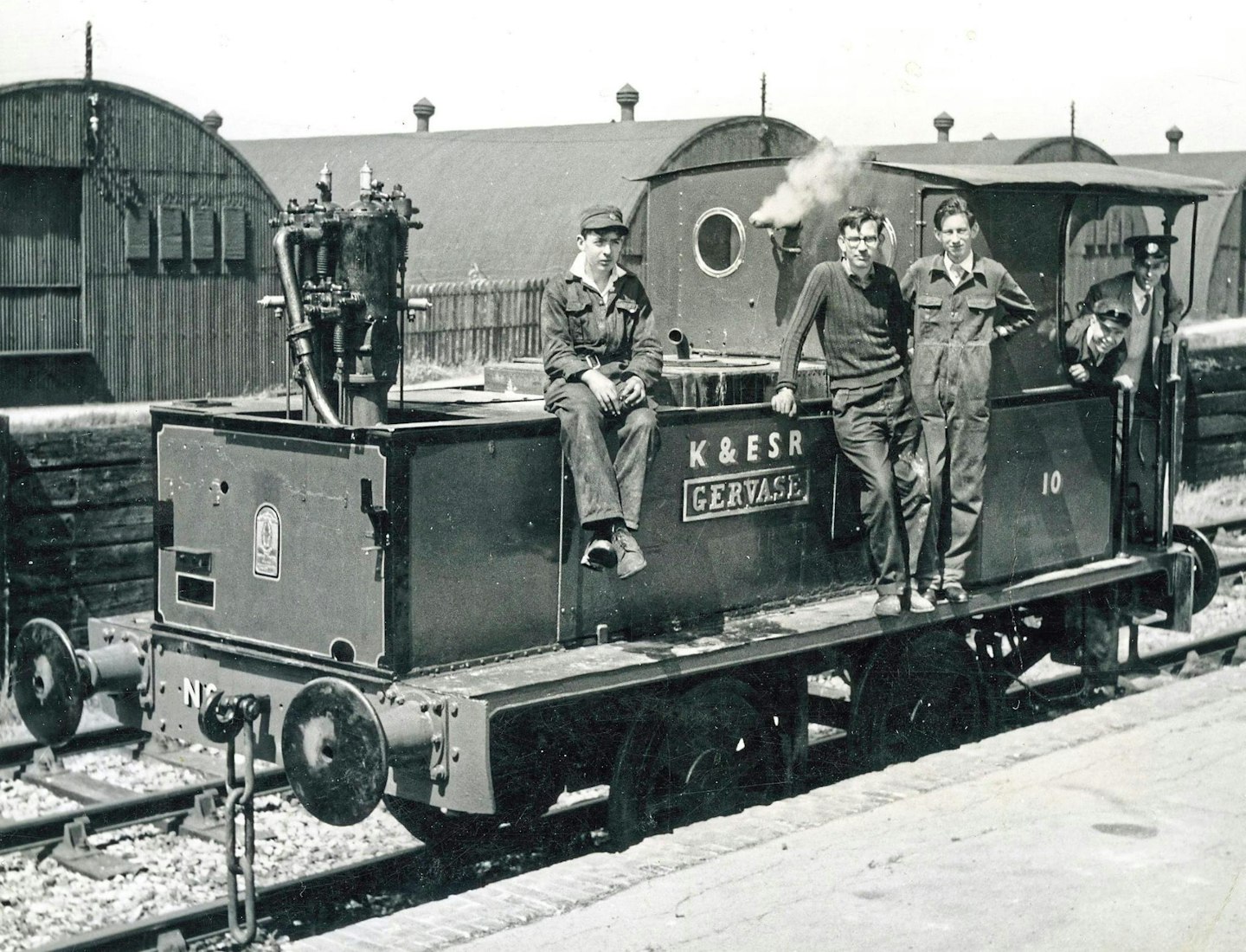

The arrival of two very unusual Sentinel locomotives – Gervase (originally a Manning, Wardle saddle tank) and former Jersey Eastern Railway railcar power bogie conversion DOM [Dorking, Oxted and Merstham, the three sites operated by Standard Brick and Sand] bolstered Alan’s interest further when they were presented to the fledgling railway society.

“We had to get permission from British Railways for them to be delivered on to site. In order to do that, we also needed to lay a siding, which wasn’t too difficult because there was rail and sleepers about. So, we were given permission to deliver these two locomotives there, but British Railways insisted they had to be chained to the track, and the track had to be separate from the railway in case we drove them away! We laid a 60-foot length of siding on the end of an existing siding, where we could chain them to the track, and then we tipped the rails out of the intervening piece between the points and our new siding – it was now disconnected from the railway. That was all right as these two locomotives didn’t work anyway.

“When we were laying the siding, two blokes turned up on a motorbike. The man on the front was the owner. His name was Dick Beckett, while his passenger was Derek Dunlavey. They were both engineering apprentices in Ashford railway works, and they had a common interest in railways. They had been to volunteer at the Bluebell Railway, but the Bluebell wasn’t interested in their engineering skills. They had them washing up in the buffet car. They thought it was all right, and it was helping out, but it wasn’t much fun.

“On their way back to Ashford, one of them, I’m not sure which, had heard about the fledgling KESR and they turned up as we were laying this siding. My introduction to Dick Beckett was when I tipped a shovel full of ballast at his boot. I said, ‘Will you get out of the way? I’m shovelling here,’ and he stood there talking. I said, ‘Oi, come on, get out of the way.’ In the end, I just tipped it down his boot. He moved. He wasn’t very happy. We were firm friends from that day until he died last year. Anyway, so they arrived, and I joined forces with them and the three of us became the locomotive department.”

By this time the railway had, in Alan’s words, ‘started to departmentalise’ with people becoming interested in different aspects such as permanent way, engineering and the commercial potential for the fledgling line. From Alan’s point of view his attention now turned to Gervase, which had been chosen as the first engine to be resurrected because it was in marginally better condition than its stablemate. Where did they start?

“We knew what a Sentinel was like because we’d acquired the maintenance book from the brick works. The first thing we had to do in order to examine the boiler was remove the firebox, which should not have been too difficult. You undo the nuts and bolts on the top, the ones on the bottom, and you lower it out. The tools came from Ashford Works. In order to get the firebox out, we had to have a pit to lower it into. So that was the next job – we dug a hole. At the siding upon which the locomotive lived, we took some sleepers out, and we proceeded to dig a hole the same depth as the firebox. Now, the problem was, at that time, the water table at Tenterden was only about a foot below the surface.

“So we dug and of course, as we dug, it got wet, and we ended up with a five-foot deep hole full of water. It didn’t matter because we were only lowering the firebox into it. It took about six weeks to get the firebox out because it was so scaled up that even once you’d taken all the nuts and bolts out, it just sat there and looked at us. We had to dissolve and break up the scale. Then we used a pulley hoist to lower it, and got it out. Of course, then we had to jack the locomotive up and take the wheels and axles out because the axleboxes were in a terrible state. Generally, we took it all to pieces.”

Juggling school

Unfortunately at this point there was no shed to work in, so the various pieces of the engine were left scattered around the yard awaiting reassembly. By now, Alan was juggling school with weekends at the station, with more volunteers coming from afar and often sleeping in the old station building.

“Then another chap turned up by the name of Dave Sinclair. Dave Sinclair was a coach builder in Ashford railway works,” remembers Alan, “he was a motivator of people, and he saw a need for somewhere for all these volunteer people to stay overnight. So, he bought a wooden coach body from Ashford Works.

“The railways never threw much away. They repurposed it. Upcycling is nothing new! In Ashford works [there were] a number of offices that were old coach bodies. The coach body that we ended up with had been the savings bank office. When you got paid, you’d go to the savings bank and put your sixpence or shilling in. Anyway, Dave said, ‘Oh, I’ve bought this coach now.’ So, we levelled some ground at the end of the platform and put some sleepers down for a foundation. Everybody mucked in and did everything necessary”

However, things didn’t go quite to plan…

“The only lorry we could have to collect the coach body was too short. So, in his lunchtime, Dave cut the coach in half with a handsaw. It took him three lunchtimes. It arrived in two bits. So, the first bit arrived… we put sleepers across to the lorry and, with crowbars and some grease, we slid it down the sleepers on to its base. Then next day, same lorry, second half. We slid that down and put the two halves together. Because Dave cut it in the right places, it could be rejoined easily and that became the volunteer accommodation.”

The coach however, needed to be fitted out. With the aid of a British Railways porter from Eltham called Terry Heaslip, it was equipped with bunks made from wagon floorboards that had been scrap at Ashford Works. At the same time, the electrification of the Kent coast railway meant that the former steam stock was being scrapped.

This, in turn, supplied seat cushions, which became the mattresses for the bunks. As Alan says, “Marvellous, isn’t it?”

Next issue – i we continue with Alan’s reminiscences about the early days at Tenterden.