CHALONER

PART ONE

While 1877-built De Winton 0 4 0VBT Chaloner may not have won the Steam Railway magazine readers’ award, it remains a hugely historic and interesting locomotive. And, it has been owned by the same family since 1960. Its saviour and owner ALF FISHER tells its remarkable story.

I had come up from Euston to Liverpool on a Friday night behind a ‘Lizzie’ with 16 bogies in tow. It was not a sparkling performance with a lame ‘Patriot’ on the Manchester relief ten minutes ahead of us, and arrival was 50 minutes late – not unusual but still unwelcome. My friend John Ward had said we were to have a day out in North Wales as he had something to show me. What he meant was that he had discovered the narrow gauge on our doorstep, or nearly.

We were approaching Mold when I was told to stop the Morris Minor, borrowed for the day from my father. We scrambled up a bank to find a little shed. Knowing John, I was not surprised to find a trio of woebegone engines in residence: two Bagnalls and a Kerr, Stuart, or vice versa. I had seen the narrow gauge a few years earlier on a solo visit to mooch around the abandoned Boston Lodge works at Porthmadog, thinking how wonderful and impossible it would be if someone could save that particular railway. Seeing these very small engines, it occurred to me that the house I had just bought had a space at the side where one of these could comfortably fit and be admired. However, I did nothing about it until John told me a few months later that they had disappeared. A quick letter to the owner, the Castle Firebrick Company, brought a quick reply telling me how disappointed they were as they had wanted to give them away to someone who would appreciate them.

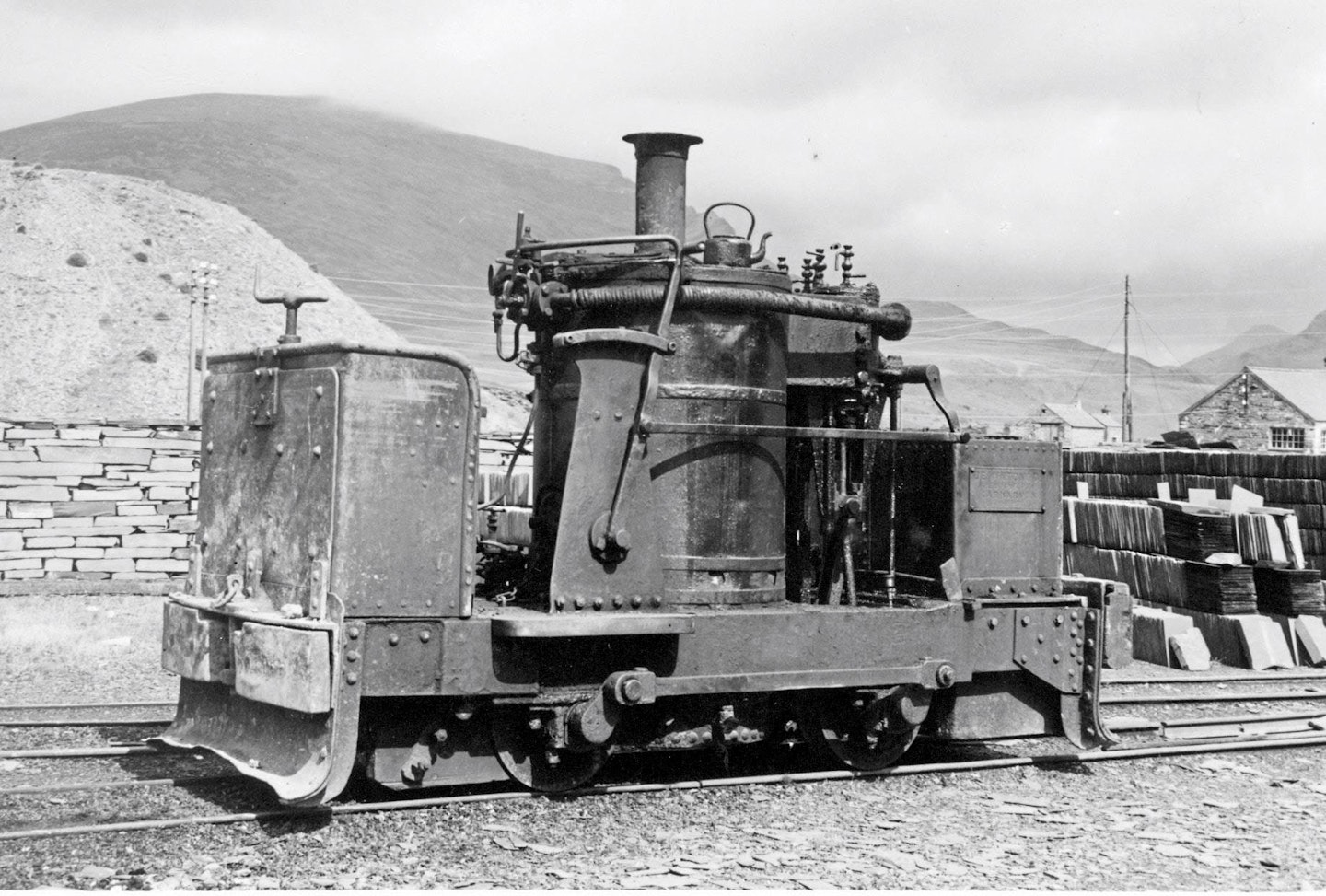

But the weird idea of buying a locomotive persisted and I contacted Penrhyn Quarry, which advised that it would be happy to sell its redundant engines for scrap value. This put them completely out of reach for me as they were valued at £10 per ton, and they appeared to be from about six tons upwards. A year or so later, John told me about some more reclusive, smaller and rather strange engines he had unearthed in the Nantlle Vale in Caernarvonshire. Mistakenly, I thought the smallest would be about two tons and, in a fit of generosity, I made an offer of £21 which, after an initial rebuff, was eventually accepted.

Hence the following saga began.

Perseverance pays off

It was 1960. I had just bought myself a steam engine, and a decidedly odd one. This was soon noticed by well-meaning friends whose response was, ‘Why didn’t you buy a ‘REAL’ locomotive?’. I suppose if I could have afforded a ‘Quarry Hunslet’, a ‘Dock Tank’ or even a ‘Jinty’, then I would have done. There was, of course, a reason – two in fact. Whatever I bought had to fit in the garage space at the side of my end-of-terrace house. Secondly came affordability. At ten pounds per ton scrap value, there was little option but to choose the smallest and cheapest I could lay hands on. And if I had bought a ‘Jinty’ I wouldn’t have owned Chaloner, and life just wouldn’t have been the same. How fortunate this turned out to be. Almost by accident, I had become the owner of an ancient piece of machinery which was to exert an influence over me and my family for the next 60-plus years.

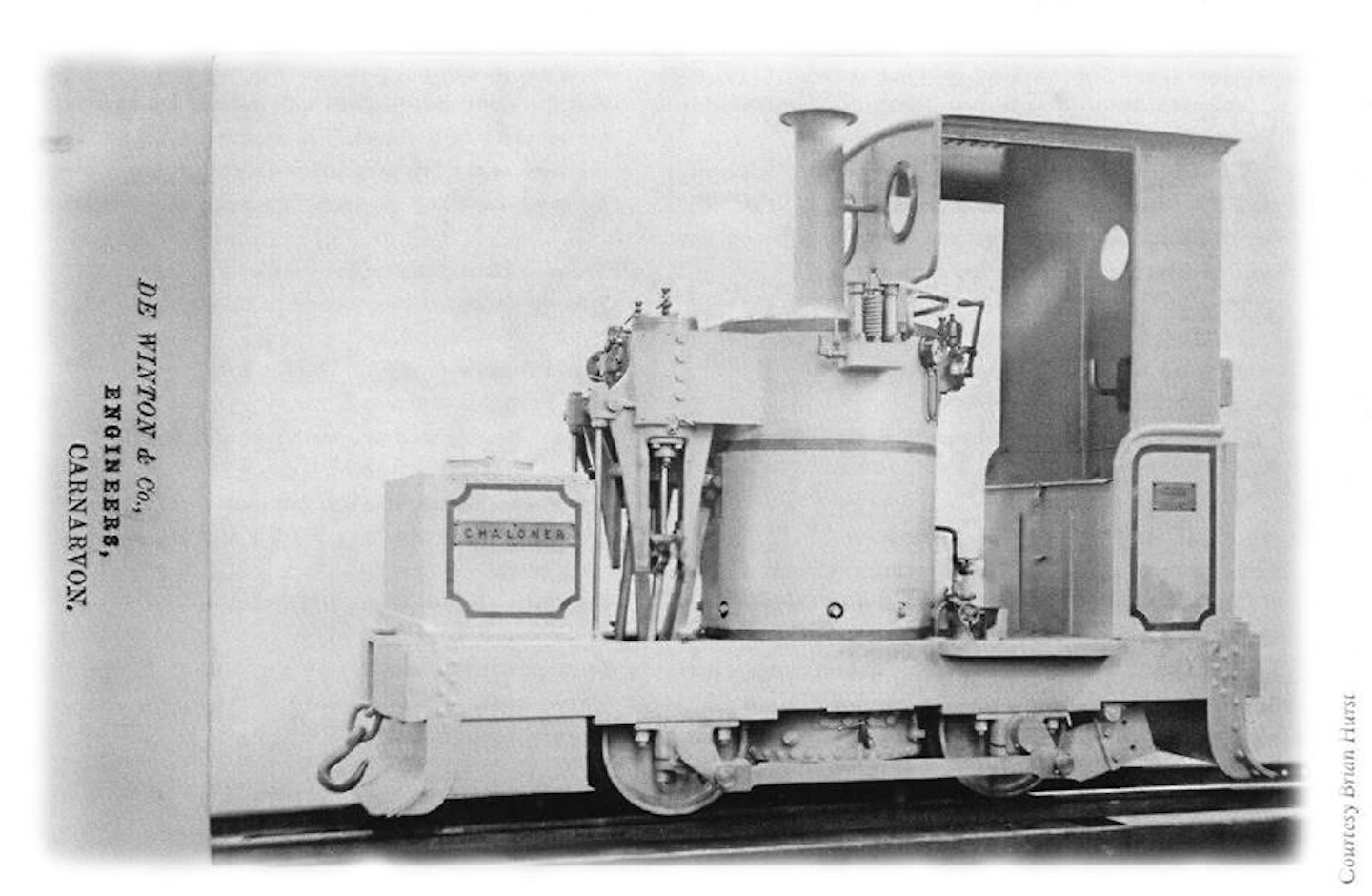

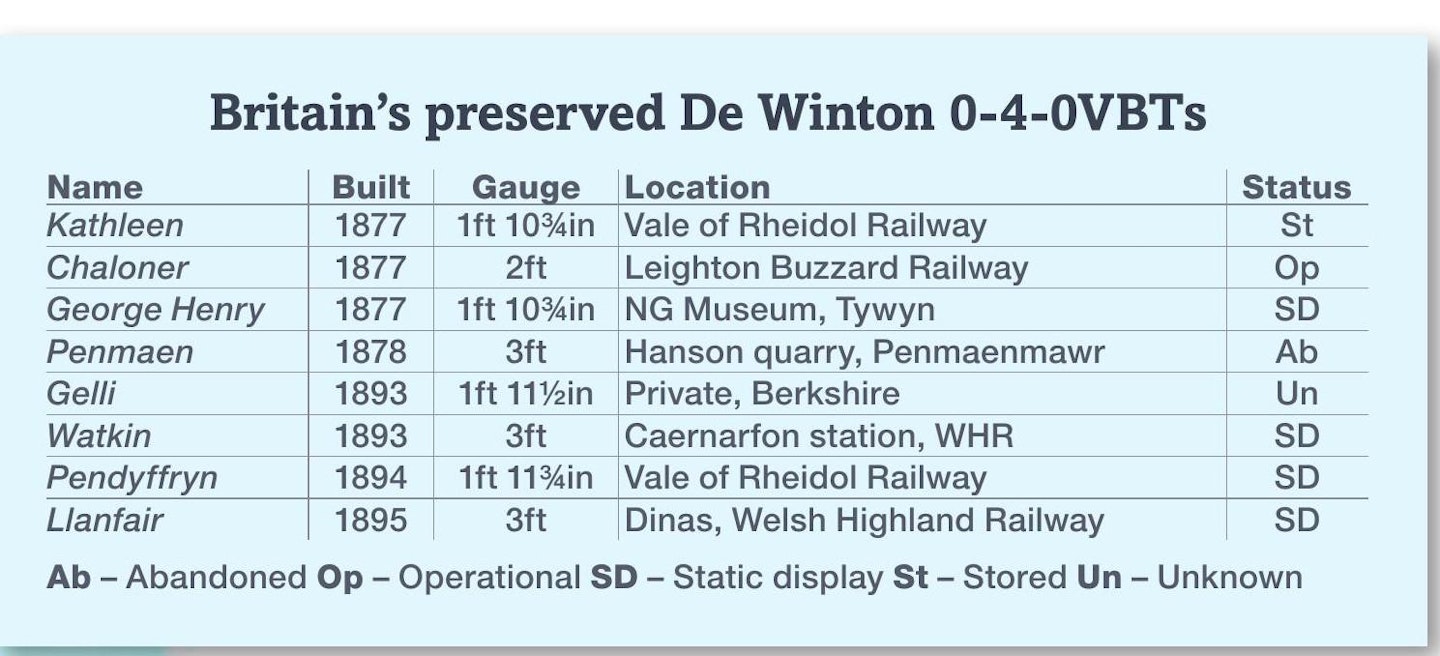

Admittedly, it was a trifle weird. The boiler was vertical, as were the cylinders. It was missing some basics one expects, such as springs, a dome and a cab. It had emanated from De Winton and Co., a small ironworks on the quay in Caernarfon in 1877, that produced machinery for the slate trade in addition to locomotives, and we now know this was the first of its new improved ‘Standard’ class. It was cheap to build and cheap to buy, thus very popular locally, and was followed by some 30 locomotives of the same basic type, including enlarged versions and an adaptation with inside frames for 3ft gauge railways. For over half a century they had pottered around the quarries of North Wales largely unloved and unnoticed.

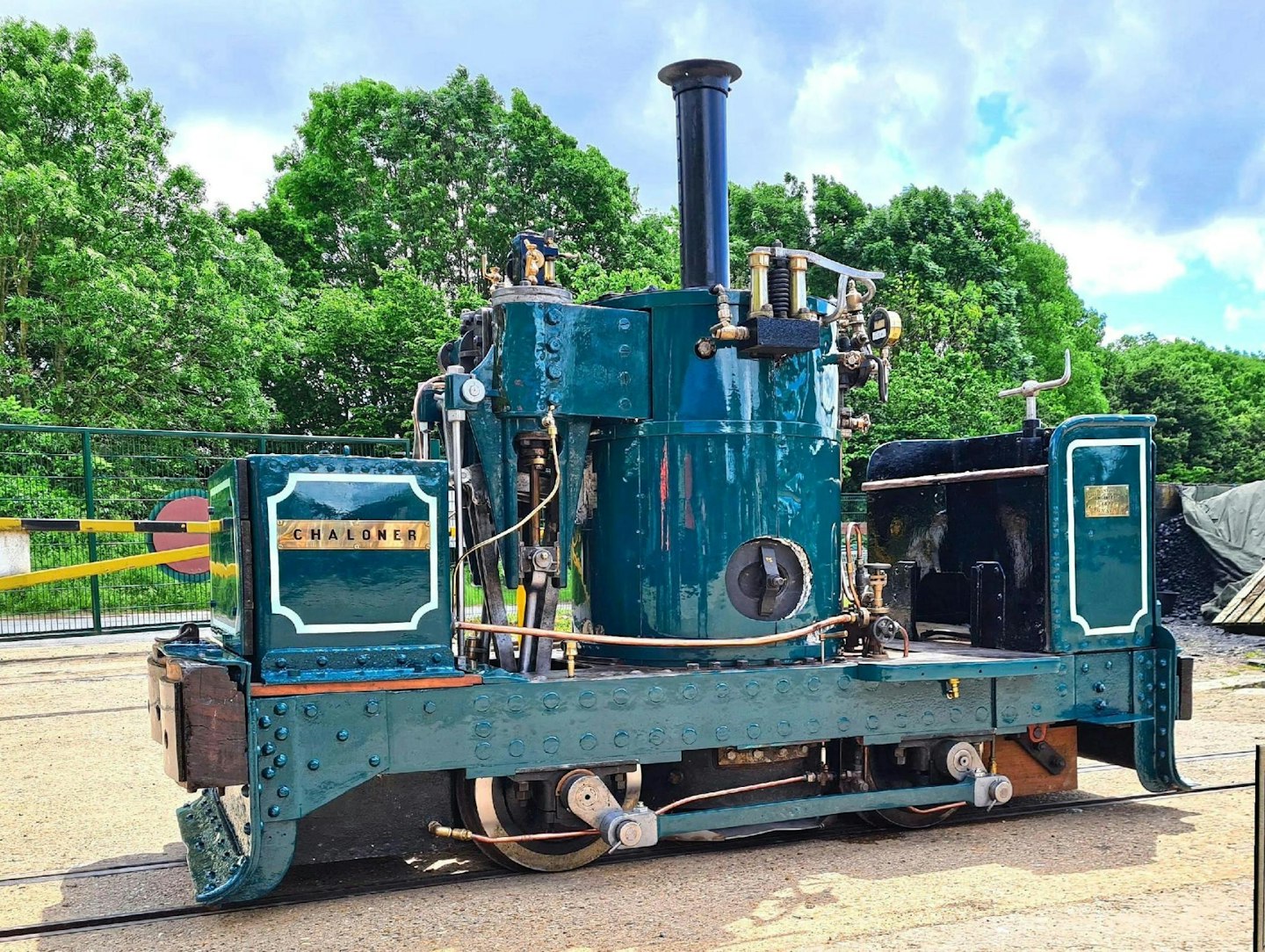

So, 64 years later, we can look back on its rescue and transformation and judge how far we have come since she became part of the Fisher family.

Like vintage car owners, locomotive owners can become totally obsessed with their possessions and spend a lifetime devoted to the object, or sadly they can start a project with great verve and enthusiasm until something more interesting comes along or funds run out – just two of the reasons for the smaller, uncared-for locomotives one sees decaying in sidings on so many preserved lines. Alternatively, you can persevere, and once you’ve overcome the feeling that everything is totally impossible you strive until something works and then you must push on to make it work even better.

So it was with me, and later with son David, but for me, with a lifelong passion for locomotives and absolutely no mechanical experience whatsoever, it was to be a long haul. Looking back, I sometimes question whether I have been the motivation for Chaloner’s revival, or if Chaloner has truly been the one in charge. Has she, like the proverbial house cat, been an apparently passive pet, or one which, like the cat, dominates the scene almost unseen?

Nevertheless, we all know that owning a locomotive needs a bottomless pit of resources, but like any hobby or sport, it can provide so many aims and challenges, so much despair, stress, anguish and yet quite unparalleled satisfaction when it eventually proves worthwhile.

Conservation mission

Anyone who has followed the progress of Chaloner will have caught on to the fact that the foremost principle guiding the care of the locomotive has always been conservation, conservation, conservation. It would be nice to say this was my noble principle from day one, but it wasn’t – it was purely accidental. Quite simply, it was due initially to a complete deficiency of funds to replace anything larger than a couple of nuts and bolts. Being only a couple of years married, with our first house, there was not much in the kitty for a frivolity such as a battered, rusty steam engine. In fact, the whole purchase of the locomotive from Pen-yr-Orsedd slate quarry in the Nantlle Vale was in dire jeopardy when I was informed that there would be an additional charge of £10 for hauling the locomotive down two inclines on a Saturday morning (overtime rates for the men), plus £35 to bring her by road on low-loader from North Wales to Hertfordshire. Added to the £21 purchase cost, the total of £66 (nearly £1,300 in today’s money) was way beyond my resources.

This was the point where Chaloner became inextricably a part of the family. As my wife had recently retired from the Met Office, she benefited from their practice of awarding a ‘dowry’ to female employees about to retire and embark on motherhood. Nobly parting with half of her £50 dowry, the deal was sealed. For her contribution, she was rewarded daily by having to gaze on a rusted hulk from the kitchen window, a hulk which slowly transformed into something more presentable.

It was always a matter of chance who would be delivered at the house first. Son David, (Chaloner’s current owner), made it first by a whisker and arrived on September 10 1960, weighing in at eight and a half pounds. Chaloner, at four and a half tons, arrived some 24 hours later. The two were fated to be inextricably linked for ever. Not every child grows up with a steam engine in the back yard. Perhaps he had little choice, and his future was already clearly defined.

We closed the road for Chaloner’s unloading by simply putting two rows of cones across it. Nobody thought that it might have been a good idea to seek permission first! The lorry simply backed into the gateway of the house and accompanied by grunts and groans from friends and neighbours, she was pushed off the lorry and on to a track panel awaiting just inside the gate.

Over the next few years, a steady stream of visitors came to see the strange object in the back yard and new friends were made. The most outstanding one usually appeared in a clerical cassock and a wore a billowing black cloak. It was of course, Rev. Teddy Boston, whose recently restored Bagnall saddle tank Pixie ran on his line through the rectory garden at Cadeby in Leicestershire.

Teddy was nothing if not forthright. ‘Alf! What on earth is the point of having a steam engine if it doesn’t go anywhere? Now get cracking and let’s see her working’. I was shocked by this order. Nothing could have been further from my mind, and the thought of getting her working filled this non-engineer’s mind with horror. But it was a challenge which could not be ignored.

Occupational hazard

So began a knuckle-crunching year, learning the hard way how to chisel out rusting tubes at both ends – all 76 of them. Neighbourly tolerance must have been near breaking point as each hammer blow resonated loudly around an empty boiler in a suburban back yard every evening. Suppliers were also tolerant and helpful. Dewrance and Co. donated two missing brass tallow cups (or oilers) while a far bigger contribution was a complete set of new tubes, gratis, from the Universal Tube Company. These were the earliest days of purchase and restoration – for context, it was two years before Alan Pegler bought Flying Scotsman. Requests for help from the trade were thus quite novel and more likely to be met with a good response.

The boiler tubes were new; the boiler was not. The holes in the tubeplates were so varied in diameter that some new tubes dropped completely through the holes to the ground below while some were tight and had to be driven in. Other tube holes were oval! This was an early lesson in how the maintenance of industrial locomotives was far removed from that of the main lines and, significantly, a foretaste of what to expect as the repair of the engine would progress.

Eventually the tubes were all inserted and expanded and the day of the boiler inspector’s visit for a hydraulic test arrived. It was to be the decisive moment, to learn if my introduction to basic engineering would pass the test. Pumping the boiler up to pressure soon became impossible when jets of water shot out from both ends of the water gauge, and I was gutted. ‘No problem’, said the obliging inspector. ‘Just pop down to the nearest garage, ask for an old inner tube, and give me a couple of sixpences.’ Puzzled, I obeyed and returned with the trophies. Removing the gauge glass and packing, he roughly cut two pieces of the rubber tube, spread them over the two openings in the water gauge, laid the sixpenny piece coins on the rubber and tightened everything up with the gland nuts. Within minutes the test was complete, and my first re-tubing of a boiler had been worth the bruises and late nights. In view of the thin tubeplate, it was agreed that she should run only at a reduced pressure of 80lb/sq. in which, to my lasting regret, we mistakenly thought would be adequate.

It may have been a foretaste of the highs and lows which were to accompany the whole restoration process, but it was a necessary prelude to raising steam for the first time in some 14 years. A fortnight later, following re-packing of the water gauge, the fire was lit, and a gathering of keen neighbours assembled to watch. With the engine raised up on blocks, the regulator was opened and to everyone’s amazement, the wheels revolved, in fact quite rapidly. Nevertheless, the onlookers were blissfully unaware of a new problem which only I encountered. The weather had produced a torrential downpour all day, meaning that observers had to watch from within the house. Despite my soaked condition, I soon became aware that every time I opened the regulator, there was a change in the nature of the heavy rain, which unaccountably turned very hot and exceedingly dirty. So, I learned another enduring lesson that, unlike conventional locomotives, these ‘Coffee Pots’ with vertical boilers do not possess a dome to collect the steam at the driest point, and that ‘priming’ – carrying boiling water with the steam to the cylinders – is an occupational hazard which must be avoided whenever possible.

To Leighton Buzzard

The incentive for me to complete the work came in 1968, being the launch of the Leighton Buzzard Railway, then known as the Iron Horse Railroad. The young volunteers were looking for a steam engine to open their railway and I happened to have one, however odd and totally unsuitable. The first test steaming on the eve of opening in June 1968 was traumatic. We put in a nice level fire and to our delight she steamed up quite rapidly – so far, so good. However, there was a slight hiccup. Yes, the safety valves blew off on cue at 80lb/sq. in, but by now there was a roaring fire, and the boiler pressure stubbornly rose remorselessly. ‘Get that injector on, fast!’. ‘It’s already been on for ten minutes!’ came the reply. There was no remedy left but to shovel out some of the raging inferno. In short, the pressure reached somewhere around 135lb/sq. in before the pointer on the gauge stabilised and started descending and life came back to normal. The following day was the railway’s opening day and was less traumatic with nothing more significant than three derailments and Chaloner characteristically misbehaving by depositing her entire fire and firebars in the middle of a main road after a particularly vicious jolt. This was never going to be like owning a ‘REAL’ engine.

To say that the early workings there were fraught would be an understatement. There was no water supply at the shed and the locomotive had to be topped up from a horse trough at Marley’s Tile Works almost a mile down the line. This was fine until one momentous day in November when we took Chaloner on a solo outing down the line to Leedon Loop, then the end of the manageable line, intending to top up on the return journey. It was extremely foggy and bitterly cold with a hoar frost all day. While waiting there, our guest – the familiar clerical figure in billowing black cloak – emerged belatedly through the fog and we decided to head back. However, every time the regulator was opened slightly, even on the level, showers of hot water were violently ejected from the chimney until water in the gauge glass was quickly invisible. All this was taking place on level track, but we still had to get her up the 1 in 24 gradient of Marley’s Bank before the water supply could be reached. With minimal regulator opening and with four people pushing her up the grade, we eventually reached the water trough. Here appeared a problem which, looking back, might have been foreseen. The trough was coated in a thick layer of ice upon which lay a frozen hosepipe. Smashing the ice, we found the water full of bits of straw, not very compatible with one ailing injector. Luckily, there was a very ancient bucket nearby. It was a mass of holes which didn’t help. It took a nail-biting time to fill the tank and the boiler to safe levels when all concerned breathed great sighs of relief – shades of the Titfield Thunderbolt. Undoubtedly having a clergyman with us with a direct line to the Almighty played a big part in our salvation, but it was a narrow squeak.

Learning the ropes

The track gauge of the still-operating sand railway on which we ran was nominally two feet but widened considerably in places. Derailments were to be expected from that fact alone, though with an unsprung locomotive, rerailing was relatively simple. However, as early as opening day it was discovered that at least one pair of wheels was oval, being a quarter inch out of true, which accounted for a bone-shaking ride. The cylinder bores were similarly worn, enabling vast amounts of steam to pass by the pistons without making any contribution to power output whatsoever. More unexpected was the fact that the front axle was 2ft gauge – the approximate gauge of its home quarry – while the other was inexplicably 1ft 10¾in. While this contributed to the unfortunate habit of falling off the rails, it also accounted for a deep groove in the Tarmac on the level crossing across the A4012. One can only conclude that Pen-yr-Orsedd Quarry had broken so many axles that it had been forced to beg help from Penrhyn Quarry (which used the lesser gauge) by providing one from its own withdrawn De Winton fleet. On removal, the offending axle was found to be cracked, and a new one was produced by the local makers of forklift trucks, Lancer Boss.

Priming was a perpetual hazard, particularly when hauling a roofless ‘passenger train’, as was the case in the first season. Many were the times that passengers returned from their ride with shirts and dresses enhanced by black polka dots, while on one occasion, water softener was added to the tank, causing foaming, which not only doubled the amount of dirty water projected from the chimney but additionally produced drops which had now become the colour of blackcurrant squash. This was even less welcome and resulted in more than one claim for compensation from angry passengers. The water softening idea was cancelled forthwith.

Lubrication was by laboriously filling small tallow cups above the cylinders and steam chests with oil before and during operations. Then one day, Teddy Boston reappeared waving a mechanical lubricator from a traction engine, which in the interests of efficiency was soon fitted and is still functioning today. For feeding the boiler, there was a single Giffard injector, which, in its worn state was somewhat temperamental and caused many anxious moments. As Chaloner was now regularly hauling passenger trains, though erratically, this was deemed a bit risky, and a modern Penberthy injector was found and fitted below the footplate. Both additions were essential changes, but for the first time the requirements of operation and maintenance had to be prioritised over the ethics of conservation.

Make do and mend

In the late ’50s and ’60s, industrial archaeology was just coming into vogue, and I was impressed by some fine books on the subject. Archaeology is not just discovering things but researching to improve our knowledge and, in some rarer cases, to revive and operate, while preserving original material at the same time. As noted, my original attitude towards conservation may have been accidental, but the growing popularity of industrial archaeology made me aware of the need to preserve original material wherever possible. It gradually dawned on me what an intriguing piece of history I had acquired, and the responsibility which went with it. Delving into the story of the locomotive, it became apparent that although all parts were of De Winton origin, many had come from other locomotives of the same or similar types, creating a patchwork of pieces which tell us much about engineering practice in the quarry, largely dictated by having to survive as the slate industry declined. Interchange of parts on main line locomotives was common for efficiency in moving engines out of overhaul as quickly as possible, but wholesale cannibalisation to make ends meet was an entirely different scenario. There was also a specific problem for those quarries with De Winton engines. Whereas top manufacturers like Hunslet or Bagnall could still supply spares for those operating their locomotives right up to the 1950s, De Winton had expired in 1901.

A few examples illustrate the point. The main frames are original apart from a replaced rear end. This may have resulted from a heavy shunt or a fall over the end of the tip. This replacement rear was already in place by 1927 when all the other De Wintons at the quarry were still in service, so where did it come from? The neighbouring Dorothea Quarry had withdrawn its three older examples by the First World War, so possibly they were the source. The two cylinders are not original but were taken from fellow locomotive Glynliffon, built in 1880, and were purloined in Chaloner’s 1926 rebuilding. The present water tank was acquired from the unique 1897 locomotive Victoria but this tank in turn had been ‘borrowed’ from an unknown locomotive of earlier vintage. The quarry records tell us that when Chaloner’s crankshaft was found to be fractured in 1927, it was replaced by one taken from Inverlochy, also built in 1877. Curiously, when this replacement shaft also failed in 1933, yet another was robbed from the very same source, yet the remarkably resilient Inverlochy survived this constant theft of its parts and inexplicably continued to run until 1938.

Sometimes, all is not what it seems. In the unique De Winton vertical boiler design, the cylinders are supported by vertical steel plates which were originally riveted to the boiler. In our case the plates are smooth and appear modern. Now, I am far from being a rivet or bolt counter, but the original works photo shows the attachment to the cylinders being by five bolts. However, the cylinders gleaned later from stablemate Glynliffon as a replacement used only four bolts with different spacing. Stripping off all paint from these support plates and the bolts themselves a couple of years ago revealed punch marks on both. Surprisingly, one bolt has five punch holes while the adjacent plate has five punch holes. So, what does that tell us? Despite three changes of boiler and a change of cylinders, the supporting plates are far from modern but original 1877 parts, as are the bolts, the original five holes in the plates having been filled in and four repositioned holes made.

Evidence of other unexpected survivals can be seen in the recent photo of the driver’s side. Circular holes can be clearly seen at the foot of the cladding, for no apparent reason. The original boiler, which was scrapped in 1927, had washout plugs for boiler cleaning in these positions, rather than large mudholes as in subsequent boilers. Yet the holes in the cladding remain, proving that with one exception, the cladding was in place long before 1927 and is almost certainly original 1877 material.

Pushing the limits

From this minefield of archaeological inconsistencies, let’s return to the family home.

With Chaloner the family pet having left, fortnightly trips to Leighton Buzzard by the male pair of the family had become the norm, compensated by sister Anne being provided with riding lessons at the same time. David, by now nine, had with other youngsters, found dubious employment at the railway by being delegated, among other tasks, to run behind the passenger train, beating out the many fires created by Chaloner in the vegetation which abounded between the rails and elsewhere. One Sunday, when I was mercifully absent, she set fire to half a cornfield. While the fire brigade relished some practice, there had to be a reason. Unlike all ‘real’ locomotives, De Wintons do not have the luxury of an ashpan, so hot cinders could, and did, drop through the firebars without hindrance.

Despite the valiant efforts of the young stalwarts at Leighton Buzzard, her age and decrepitude began to tell. In 1970, work was done to improve the slide valves and port faces but all within stringent financial limits. The chimney was extended back to its original height so that drivers could at last go home without bleary bloodshot eyes from the smoke and ash – times when we admittedly wished for a ‘real’ engine with a chimney at a respectable distance.

The early ’70s saw a succession of crises – broken crankpins, a cracked mudhole door, a cracked axle, a fractured steam pipe, and, in 1972, the last straw came, when a pin decided to detach itself from an expansion link while running an enthusiasts’ special, causing damage to the motion which led to an enforced slumber for three years.

**

Next time:**

● Alf covers Chaloner’s resurrection, its recent heavy rebuild, and some of its most incredible journeys.

Each issue of Steam Railway delivers a wealth of information that spans the past, present and future of our beloved railways. Featuring stunning photography, exclusive stories and expert analysis, Steam Railway is a collector's item for every railway enthusiast.

Choose the right subscription for you and get instant digital access to the latest issue.